Anurendra Jegadeva

Year of birth: 1965

Origin: Johor, Malaysia

About the artist

Anurendra Jegadeva’s art deals with a number of themes that branch out from the central issue of identity. He dips into his own Ceylonese-Tamil descent as a springboard to address wider issues; for instance, the disharmony between the Tamil Tigers and Sinhalese Monks in Sri Lanka (as illustrated in his Militant Monk (2001) series), whereas a slightly dissimilar type of strife is addressed in Tribute and Fat Jentayuh Lost in Geelong (both 2004).

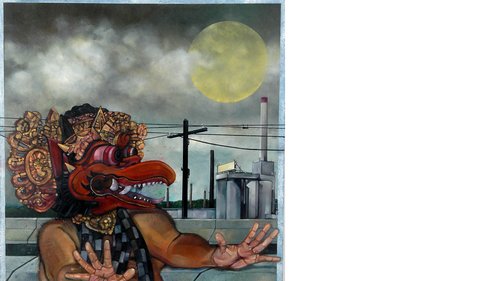

Both paintings feature a male figure wearing a Balinese barong mask (traditionally used in dances) and are self-portraits after a fashion, featuring the artist’s own body placed within contexts that are at odds with the cultural symbol. In Tribute, he tunes into an iPod against a checkerboard background, whilst the other painting sees ‘Jentayuh’ (or, ‘Jatayu’, the demi-god described in the Hindu epic, Ramayana), retches, as if lost, in the unfamiliar urban environment of Geelong in Victoria, Australia.

These works confront contrasts, alienation, and displacement - all topics that pertain to the artist’s own life during this period.

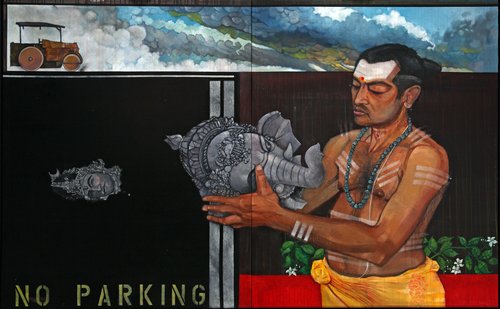

Anurendra Jegadeva migrated to Australia in the late 1990s and these artworks mark the tail end of this sojourn. He returned to Malaysia in 2005, and similar emotions surfaced again. The large diptych, No Parking (2007), bears testament, broadly remarking that progress and globalization leave little room for culture and traditions, whilst referring directly to the demolishment of several Hindu temples in Kuala Lumpur a year before the artwork was produced.

It depicts a Hindu priest holding the head of a statue of Lord Ganesha. Another beheaded statue, with tractor and clouds of smoke in the background, conjure the events leading to this outcome. Indeed, Anurendra has been recognized as one of the few Malaysian artists to have directly addressed issues pertaining to Malaysian-Indians, a racial minority in this country.

“I have always believed that you paint, write, and talk about what you know... art is a cultural product.

Indian is what I am and the socio-political dynamics of this country shapes the communal thinking, which periodically either celebrates or abhors difference. That is what I continuously search for through the work, a mixture of cliché, corrections, and deceit,” states the artist.

His seminal work, Running Indians and the History of the Malaysian Indian in 25 Clichés (2001), offers a good summary of this statement.

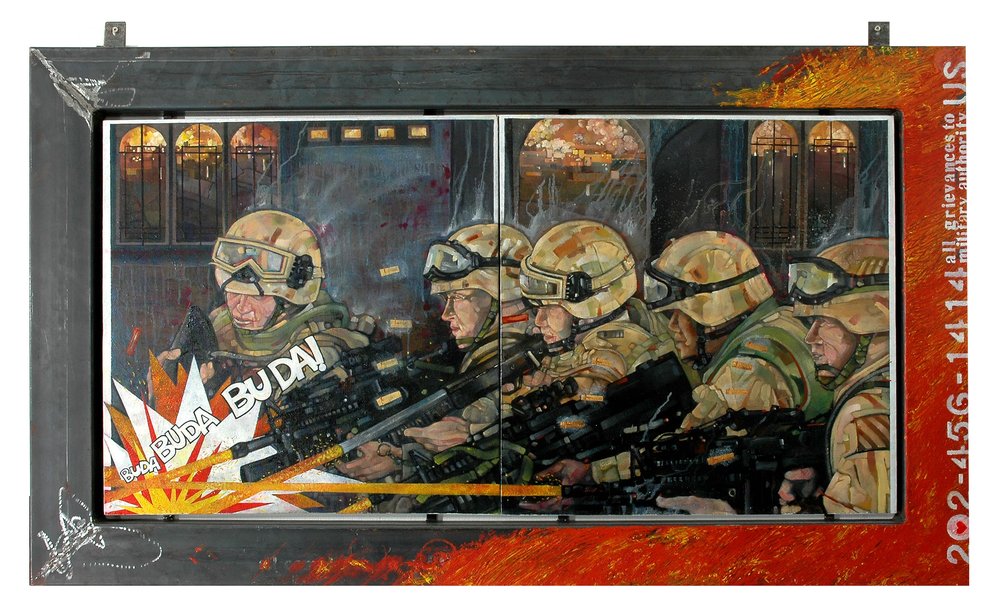

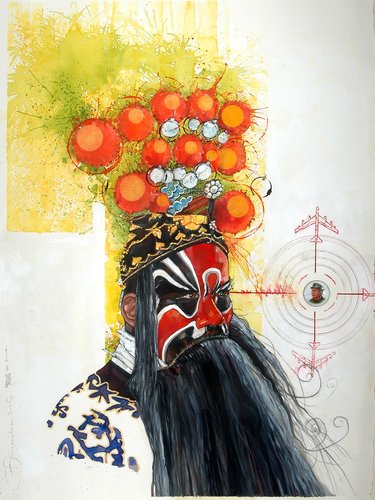

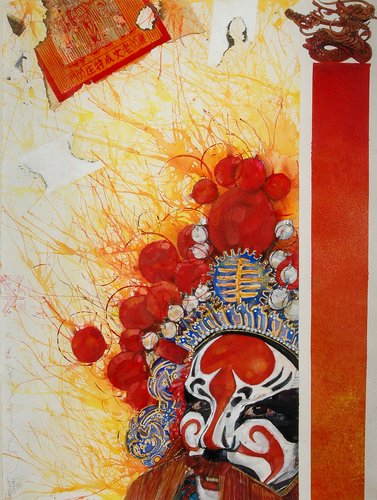

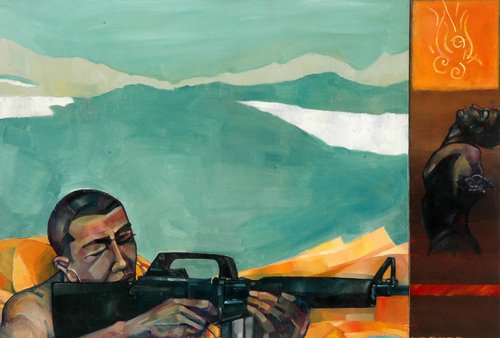

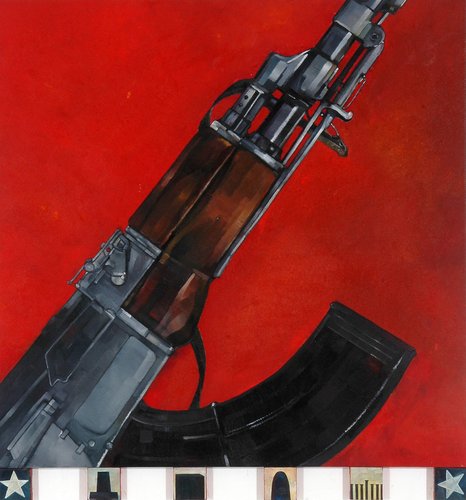

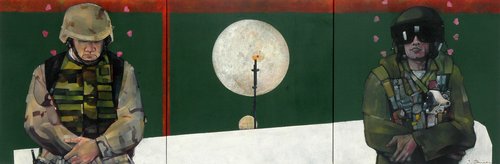

No Parking was exhibited in the artist’s fourth solo, Conditional Love, in 2008. This exhibition saw a number of his older subjects revisited, such as Chinese opera masks (earlier versions of this are from Series A [2005] and military-themed paintings, whose predecessors include Sentinels at the Temple of Oil (2004) and NO TITLE IN BOOK? (2006). They are products of the artist’s observations of the world as depicted in the mass media and culture, particularly television, which has been inundated with images of war in the last decade.

A religious element in visible in these works (and many others by Anurendra), which have borrowed the diptych and triptych format of Christian altarpieces; the arch of hearts surrounding the soldiers in Sentinels at the Temple of Oil are reminiscent of the golden halos in Christian art.

The oil tower in the centre mimics the placement of the crucifix. Unlike the solemnity of religious art, however, Anurendra has utilized pop-like imagery.

This treatment pushes forward the notion that the media has sensationalized events of gravity with such liberty that they have become spectacles for the public. Anurendra has been labelled a storyteller, a reference to the strong narrative of his works.

However, the artist demurs by stating: “The whole idea of storytelling is still very much alive within the Southeast Asian folk traditions.

Since there are so few writers here, it is a form of documenting our oral histories.”

In fact, the multi-faceted artist has documented these stories - and the history of Malaysian art - via his role as an art critic with one of the country’s leading newspapers, where he published texts as ‘J Anu’ for over nine years. He’s also worn the hat of a curator in Australia and Malaysia.

His debut show here was Figurative Traditions in Modern Malaysian Art. In his evolution as an artist, he credits influences from artists Redza Piyadasa and Jolly Koh (who taught him the fundamentals, especially the workings of colour), the Matahati art collective, and the figurative works of Ahmad Zakii Anwar and Euan Uglow (English figurative painter, 1932-2000).

Education

2002Master Of Fine Arts

Monash University Australia

1993Llb (Honours)

London University United Kingdom

1986Foundation In Art And Design

Oxford Polytechnic United Kingdom

Artworks

Night Visit At Haditha (2006)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Divine Vessel I (2006)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Letter From Dave (2006)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Scorched Earth (2005)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Flaming Funk (2005)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Emperor's Cheek (2005)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Airy Fairy (2005)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Grandmother (1998)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Militant Monk In Red Outline (2001)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Militant Monk I (2001)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Large Militant Monk (2001)

Anurendra Jegadeva

New Gods, Old Gods (2002)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Fat Jentayuh Lost In Geelong (2004)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Tribute (2004)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Fine Line (2004)

Anurendra Jegadeva

Sentinels At The Temple Of Oil (2004)

Anurendra Jegadeva

The Promise (2005)

Anurendra Jegadeva

No Parking (2007)

Anurendra Jegadeva

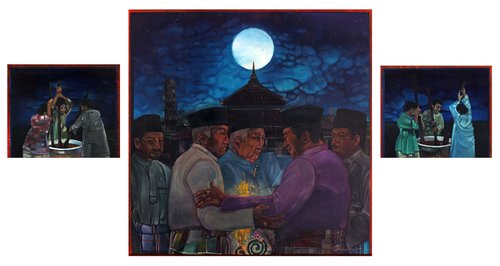

For The Love of Ghee Temple Congregation (2010)

Anurendra Jegadeva